Report | Pursuing Digital Agency in the Era of Pervasive Surveillance and Disinformation

Date and Time: Monday, April 28, 2025 Time: 14:00-16:00 (8:00-10:00 CEST & GMT+2)

Venue: Zoom online forum

Forum Language: English

Speakers:

Dr. Lungani Hlongwa, Independent Researcher

Dr. Aqsa Farooq, Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Amsterdam

Moderator:

Katarzyna Szpargała, Doctoral Candidate, Institute of Social Research and Cultural Studies/ Researcher at the International Center for Cultural Studies, NYCU, Taiwan

Organizer:

International Center for Cultural Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University

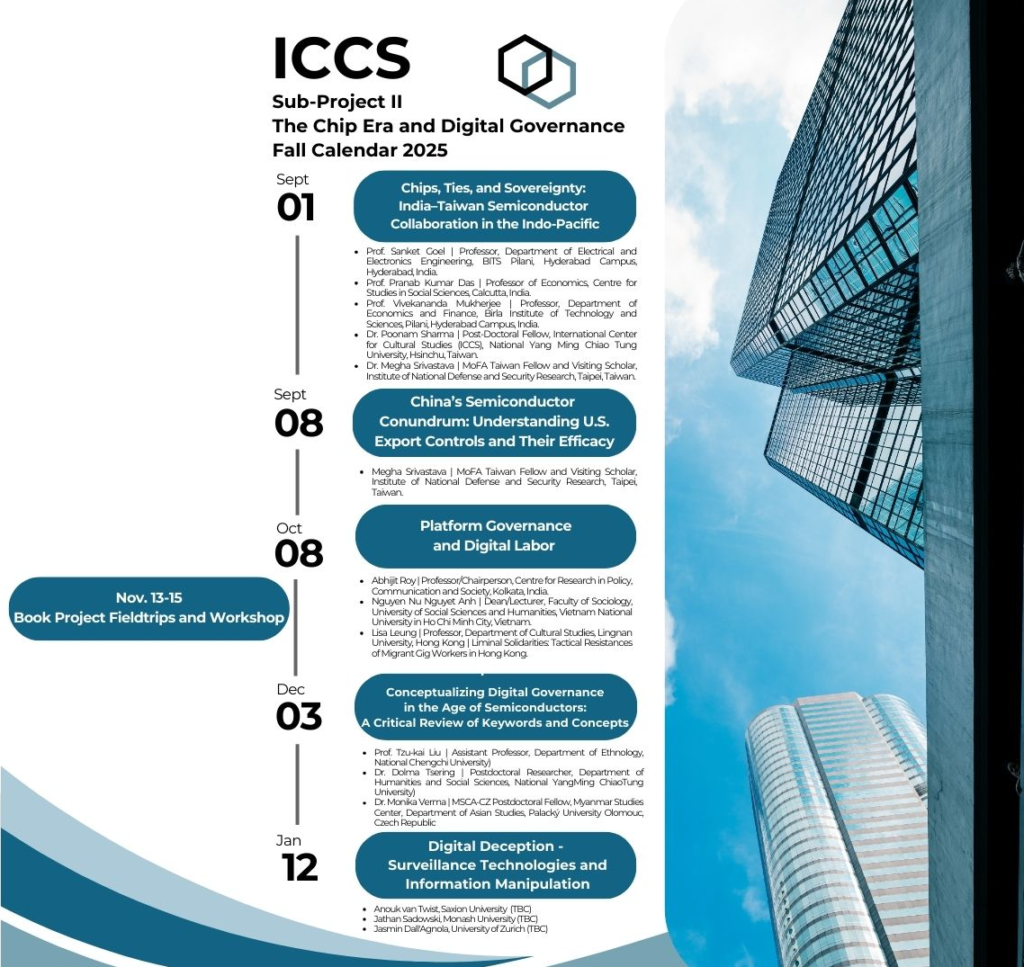

Subproject II: The Chip Era and Digital Governance (Principal Investigator: Joyce C.H. Liu)

經費來源:教育部高等教育深耕計畫

Reported by: Hanna Hlynenko (MA student, IACS)

On April 28, the International Center for Cultural Studies held an online forum “Pursuing Digital Agency in the Era of Pervasive Surveillance and Disinformation” as a part of Subproject II: The Chip Era and Digital Governance. The forum brought together scholars to discuss how global digital power dynamics are reshaping state-citizen relationships and influencing emerging models of digital governance.

Lungani Hlongwa. Hikvisionary Urbanism and the Patenting of Social Control

Over the past two decades, Chinese companies have been actively building digital infrastructure across the globe. A particularly prominent aspect of this expansion is the development of Smart Cities, and specifically Safe Cities, which are designed to provide urban surveillance technologies to city governments under the premise of fighting crime. In Africa, several Chinese companies, including Hikvision, Huawei, ZTE, Cloudwalk, and Dahua, have played key roles in deploying surveillance technologies. Their expansion in the region carries a range of socio-political and geopolitical implications, including concerns around legality, privacy, technological accuracy, and governance impacts.

Independent researcher Lungani Hlongwa conducted fieldwork in Johannesburg, uncovering various pull factors that attract these technologies to the city. These include urban development strategies centered around the Smart City model and the involvement of local entrepreneurs who collaborate with transnational suppliers. Push factors such as “donation diplomacy”, in which Chinese companies sponsor trips for city officials to observe Safe City operations in China, also play a role in technology adoption.

Some of the surveillance cameras provided by Chinese firms feature facial recognition technology that is still under development and remains prone to accuracy issues. However, this fact is often not mentioned in their architecture. Among other problems associated with these cameras are racial profiling and the potential use of these technologies for political suppression.

Describing the way surveillance technologies reshape urban life, governance, and socio-political realities in Johannesburg, Lungani Hlongwa introduced the concept of Hikvisionary Urbanism. This term captures the role of Chinese tech companies in transforming the city into an “urban panopticon.” To explore this phenomenon, Lungani Hlongwa employed Critical Patent Analysis, which treats patents as social artifacts embedded with ideological and philosophical visions. Patents are examined both quantitatively and qualitatively to reveal the socio-political intentions of their creators and to trace how global technological strategies materialize in local contexts. This research showed a significant increase in Hikvision’s patents since 2014, not only in conventional surveillance technologies but also in experimental areas like facial recognition. Moreover, Hikvision has moved to monopolize the standardization of facial recognition technology at the International Telecommunication Union.

Key patents uncovered in Lungani Hlongwa’s study include:

Method, Device, and Equipment for Determining Correlation Degree Between Personnel and Event, which uses historical data such as case logs and public information to link individuals to specific events by matching behavioral patterns. While aimed at aiding crime investigation, it raises serious concerns over privacy, freedom of expression, and religious rights. It was controversially applied in a “smart campus” project to monitor minority students.

Emotion Recognition Method, Device, Equipment, and System: This patent enables the detection of emotional states using data from facial expressions, body language, and vocal tone. Based on scientifically flawed assumptions that facial expressions reliably indicate emotions, this technology raises ethical risks and could lead to biased surveillance and discrimination. It has been linked to human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Intelligent Establishment Method for Asian Face Database: This technology builds facial recognition databases specifically for Asian faces. It raised concerns about consent, data privacy, and the potential to create databases for other ethnic groups. This technology may reinforce racial bias and automated racism in surveillance systems.

Lungani Hlongwa identified three primary concerns regarding the patenting of surveillance technologies for social control. First, it turns surveillance into property: patents protect technologies that monitor, predict, and control public behavior. Second, it normalizes control, embedding urban monitoring as a standard feature of modern city life. Third, it poses threats of racial profiling, privacy violations, and suppression of dissent. He also provided voice clips from his interviews with an IPVM technology expert and a social justice activist, both of whom shared their perspectives and expressed concerns about these developments.

Lungani Hlongwa defined digital agency as the capacity of actors – governments, institutions, civil society – to negotiate, influence, and shape their digital future. He argued it can be pursued by diversifying technology partners, negotiating equitable partnerships, strengthening data protection laws, and leveraging regional regulatory frameworks.

Caption: (Top left) Speaker Aqsa Farooq; (Top right) Speaker Lungani Hlongwa. (Bottom left) Moderator Katarzyna Szpargała; (Bottom right) ICCS Director Joyce C.H. Liu.

Aqsa Farooq. “Information Chaos,” Generative AI and Citizens in the EU

Shifting the focus from the Global South to the Global North, Aqsa Farooq, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Amsterdam, explored the informational threats posed by generative AI from a citizen-centered perspective, particularly in the context of elections.

In Europe, the “Big Election Year” of 2024 sparked widespread media concern about the potential dangers that generative AI poses to democratic processes. The World Economic Forum Global Risks Perception Survey 2024–2025 revealed that experts now rank misinformation and disinformation as the top short-term global risks, surpassing even extreme weather events.

Aqsa Farooq clarified key definitions: misinformation refers to unintentional mistakes or inaccuracies, disinformation involves fabricated or deliberately manipulated content, and malinformation is the intentional release of private information for personal or strategic gain. All three forms, she emphasized, can obstruct citizens’ access to reliable information and thus undermine democratic participation.

The spread of AI-generated disinformation has escalated alongside the growing accessibility of generative AI tools. Such content has been used in political disinformation campaigns and in promoting hostile narratives targeting vulnerable communities, not only by individual actors but also by authority figures. One notable example includes AI-generated deepfakes of Keir Starmer and Prince William, circulated on social media as part of a cryptocurrency scam.

In 2024, AI-generated disinformation appeared across numerous electoral contexts around the world. Specifically, incidents involving fake images, audio clips, and text emerged during political campaigns in the UK, Slovakia, and Poland. In response, major digital platforms, including Google, Meta, and TikTok, launched targeted strategies to counteract disinformation in the lead-up to the EU elections.

The campaigns of the European Elections of 2024 revolved around the same type of anxious language. Despite this alarmist rhetoric, data from the European Digital Media Observatory shows that AI-generated disinformation never exceeded 5% of the total disinformation identified in the year preceding the EU elections.

Aqsa Farooq’s research, conducted in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Amsterdam, investigated how AI-generated disinformation may influence citizen behavior and engagement during elections. The research featured samples of responders from Germany, the Netherlands, and Poland who were surveyed over the course of the elections. Citizens in Germany and the Netherlands expressed the highest levels of concern about generative AI’s impact, while respondents in Poland reported the highest frequency of encounters with AI-generated disinformation, as well as the most deliberately misleading content. Polish respondents also expressed the most significant concern over electoral fairness. Overall, the volume of AI-generated disinformation increased as elections approached.

Aqsa Farooq also identified the most common themes of AI-generated disinformation: climate change and mass immigration. For instance, AI-generated images depicting large crowds of immigrants were used by some political groups to provoke fear and reinforce anti-immigration sentiments. When asked whether it is acceptable for politicians to use AI-generated images to illustrate perceived threats, respondents from all three countries were more likely to approve such usage when it aligned with their own political beliefs.

According to a report by the Alan Turing Institute and the Centre for Emerging Technology and Security, only 16 viral incidents of AI-enabled disinformation were confirmed during the UK elections, and just 11 cases were identified in the EU and French elections combined. Based on these numbers, the report concluded there is no substantial evidence that AI-generated disinformation had a meaningful impact on the outcomes of these elections.

However, the report did highlight more insidious risks, such as the use of AI to incite online hate against political figures, its damaging effect on public trust in online information sources, and unmarked uses of AI-generated materials by politicians in campaign advertisements. The report also identified new specific types of misuse of AI, which result in additional risks, such as satirical deepfakes being misinterpreted as factual, authentic political content falsely flagged as AI-generated, and deepfake pornography used to smear political candidates. These developments suggest that while the quantitative impact of AI-generated disinformation is limited, the qualitative risks to public trust and individual rights are tangible and call for further research.

Q&A and discussion session

In the discussion session, Aqsa Farooq reflected on the European Union’s relatively strict regulatory approach to technology, which, she argued, provides the EU with a degree of resilience against external attempts to manipulate elections. Lungani Hlongwa elaborated on already observable socio-political consequences of Hikvisionary Urbanism, including racial profiling and broader security concerns tied to surveillance infrastructure.

The discussion between the speakers and the audience turned toward the broader implications of living in a technological era where significant power is concentrated in the hands of unelected technocrats. The conversation also addressed the role of counter-surveillance organizations and movements and the implications of different architectures of generative AI models. This state of affairs demands precise regulation around questions of who controls digital platforms and who has access to the data. The session emphasized the importance of continuous public education and the empowerment of regular citizens to ensure democratic oversight in the digital age.