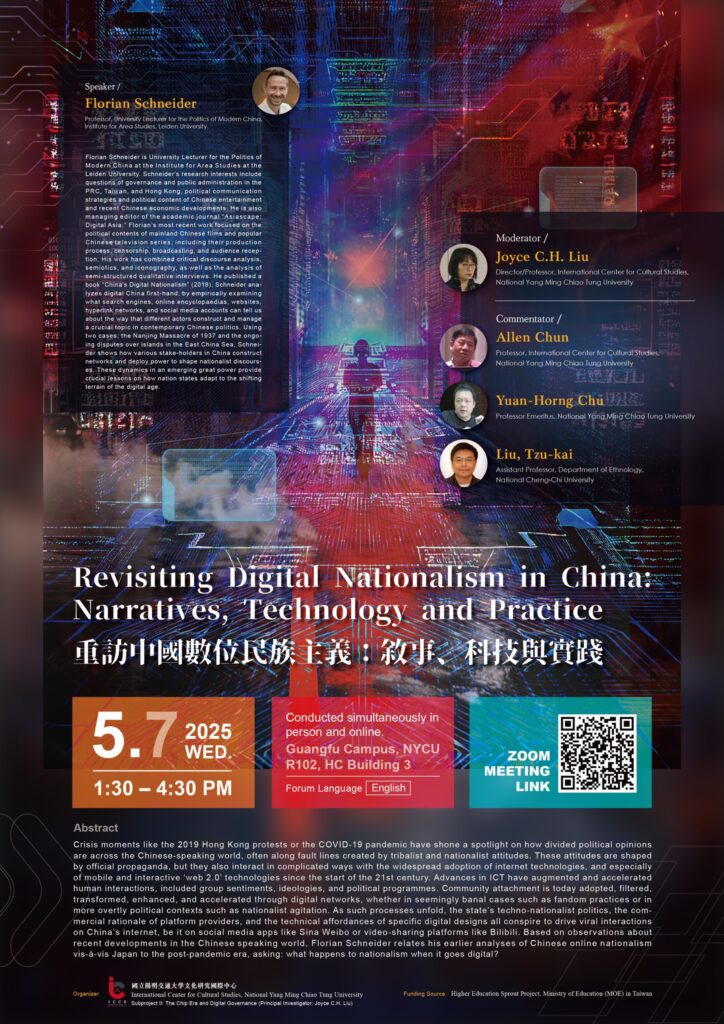

Report | Revisiting Digital Nationalism in China: Narratives, Technology and Practice

Date and Time: Wednesday, May 7, 2025, 13:30 – 16:30 (Taipei Time)

Venue: Room 102, HC Building 3, Guangfu Campus, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University

Forum Language: English

Speakers:

Florian Schneider (Professor, University Lecturer for the Politics of Modern China, Institute for Area Studies, Leiden University)

Moderator:

劉紀蕙 Joyce C.H. Liu (Director/Professor, International Center for Cultural Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University)

Commentator:

陳奕麟 Allen Chun (Professor, International Center for Cultural Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University)

朱元鴻 Yuan-Horng Chu (Professor Emeritus, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University)

劉子愷 Liu, Tzu-kai (Assistant Professor, Department of Ethnology, National Cheng-Chi University)

Reported by: Yen Chun Chen (MA student, IACS)

This lecture was given by Professor Florian Schneider from Leiden University, the Netherlands. His central question was: “What has changed in nationalism after its digital transformation? Is it still a continuation of traditional nationalism, or has it entered a new stage?” Schneider emphasized that contemporary Chinese nationalism should not be reduced to a single, linear instrument of authoritarian rule. Instead, it must be reexamined through the lenses of narrative strategies, technological mediation, and collective practice. By analyzing concrete cases, the lecture revisited how digital nationalism is enacted and reflected on how such changes continuously reshape the landscape of nationalism in China.

Historically, nationalism has been understood through collective trauma and territorial disputes, such as the Nanjing Massacre or the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands conflict. Today, however, nationalism is enacted and reproduced through everyday life. In line with Michael Billig’s concept of banal nationalism, these practices operate subtly through online culture, algorithmic curation, and fan community interactions. Using Sino-Japanese historical memory as a case, Schneider revisited his earlier research on how events like the Nanjing Massacre(南京大屠殺) and Diaoyu disputes(釣魚台爭議) have been emotionally mobilized in China’s online space. For instance, the 2012 anti-Japanese protests were accompanied by a flood of hostile discourse on social media, where narratives of territorial anxiety merged with historical trauma to evoke intense nationalist sentiments. These emotional responses were not spontaneous but amplified through platform design, algorithmic sorting, and state guidance. For example, Baidu listed the Diaoyu Islands under Fujian Province’s weather reports and even offered a mock “book your trip to Diaoyu” feature, subtly reinforcing its sovereign claim. This mode of operation corresponds to Benedict Anderson’s notion of imagined communities, wherein national belonging is shaped by shared narratives and symbols, and in the digital age, these symbols circulate via technological media and perceptual environments.

How does digital nationalism permeate everyday culture? Schneider offered the case of actor Xiao Zhan(肖戰)’s fan community, whose internal conflict revealed how bottom-up emotional mobilizations could influence policy. Xiao’s costume drama The Untamed(陳情令), loosely depicting homoerotic undertones, attracted fans with divergent positions on gender and sexuality. Disputes over fan fiction led to mass reporting of content and ultimately caught the attention of authorities, resulting in the shutdown of related platforms. This shows how grassroots pressure can drive cultural governance. Beyond this, Schneider analyzed the COVID-19 pandemic period, when nationalism manifested through platform-mediated emotional mobilization. On the video platform Bilibili, comments like “Wuhan jiayou(武漢加油)” and “Go China” flooded news videos. These comments formed algorithmic feedback loops that reinforced national solidarity and identity within the community. Such mobilizations were not solely state-directed but emerged from collective user participation. Here, nationalist discourse becomes not just a state-centered project but a cultural practice that can be mimicked, performed, and appropriated.

Thus, digital nationalism is not only evident in content production but is deeply embedded in the technological and structural design of platforms. Through search result manipulation, geographic labeling, and comment-ranking systems, national identity is normalized as the “default” perspective. These biases are not merely technical artifacts but ideological constructions co-produced by the state, platforms, and user communities. Therefore, nationalism becomes embedded in the routine logic of digital operation, an unconscious norm. These phenomena illustrate how nationalism is inscribed into the material and symbolic infrastructures of everyday digital life.

Schneider concluded with Manuel Castells’ theory of the network society, arguing that governance in contemporary China has shifted from direct opinion control to strategic intervention at multiple networked nodes. The state now exercises switching power and programming power, enabling it to guide speech not through overt censorship but via platform design, language conventions, and cultural assumptions. Citizens are thus subtly led to “voluntarily” speak correctly and imagine the nation in state-sanctioned ways. Digital nationalism is not a new phenomenon, but it is now operating in profoundly new forms. To understand contemporary China, one must grasp this restructuring of power that emerges at the intersection of technology, emotion, and politics.

In the final part of the lecture, discussants engaged in a multifaceted conversation from the perspectives of cultural studies, political economy, and technological governance, aiming to further delineate the conceptual boundaries and analytical possibilities of digital nationalism.

Professor Tzu-kai Liu focused on how nationalism is continuously reproduced as a form of everyday digital practice. He observed that internet users participate in the dissemination and standardization of nationalist narratives through emojis, memes, hashtags, and reposting, practices that are deeply embedded in platform operations and the habitual logics of digital language. Particularly within China’s post-socialist context, Liu argued, nationalism intertwines with consumer culture to form a new ideological contradiction. For example, during commercial events such as Singles’ Day (Double 11), platforms frequently mobilize socialist and nationalist language to stimulate consumer desire while resonating with patriotic sentiment, constructing what he termed “consumer nationalism.” Drawing on Lisa Rofel’s concept of the desiring subject, Liu further highlighted how Chinese public culture and visual politics use digital platforms to construct subjectivities oriented toward national belonging. He also called attention to digital laborers who are not typically seen as political actors (such as fans or delivery workers) but who nonetheless contribute to the propagation of nationalist discourse through their everyday interactions. The problem with banal nationalism, he emphasized, lies in its imperceptibility: it quietly reinforces exclusion and standardizes national subjectivity through repetition and normalization. Schneider agreed with this assessment and noted that such complex participatory dynamics reflect the decentralized power relations described by Actor-Network Theory (ANT). Digital nationalism, in his view, is not a top-down product of state ideology but an emergent formation shaped by platform architecture, user practices, and linguistic norms. Its logic resembles that of a distributed system more than a vertical hierarchy.

Professor Yuan-Horng Chu raised concerns about the Chinese government’s increasing reliance on social media data as a proxy for public opinion. He asked whether these online “patriotic surges” truly reflect civic sentiment or are merely the amplified outputs of algorithmic echo chambers. He also reminded the audience that there is historical precedent for nationalist sentiments turning against the state itself, most notably the May Fourth Movement of 1919, when patriotic students, angered by the unequal Twenty-One Demands from Japan, directed their protests at officials of the Beiyang government. This potential for nationalist backlash has long been a source of concern within the Chinese Communist Party. In response, Schneider recalled his earlier research on Chinese media policy, noting the self-reinforcing and fictitious nature of certain data systems. Even when fabricated ratings were widely acknowledged as false, policy decisions were still based on them. Likewise, he argued, popular discourse on social media should not be mistaken for genuine public opinion; instead, we must analyze how visibility and virality are jointly produced by platform structures, recommendation algorithms, and discursive templates.

Professor Allen Chun challenged the conceptual precision of “digital nationalism” as a term. If it merely denotes a digitized form of traditional nationalism, its analytical utility is limited. But if it seeks to address the structural transformation of nationalism through digital technologies, then greater clarity is needed to distinguish it from adjacent terms such as patriotism, cultural chauvinism, or collective emotional expression. Many phenomena labeled as nationalism, Chun noted, may simply be platform-induced emotional responses without deeper ideological content. In response, Schneider explained that his work differentiates between related terms: techno-nationalism at the policy level, cyber-nationalism as digitally mobilized activism, and online nationalism as discursive practice in forums. His notion of digital nationalism, however, emphasizes infrastructural shifts, how platform design influences information flow, amplifies voice, and reconfigures group boundaries. It is this interplay between digital environments and political effects that Schneider views as the most urgent site of investigation.

In conclusion, digital nationalism in the contemporary era derives its power not merely from its content but from its embeddedness in the design of digital platforms and in everyday social interactions. It is rendered omnipresent and seemingly natural, difficult to detect, and easily internalized. As such, the operations of ideology become normalized and accepted. These processes are deeply shaped by platform design, user habits, and policy interventions. Researchers must remain vigilant to the governing logic that emerges from the entanglement of technological structures, emotional mobilization, and political power. It is precisely in these silent mechanisms that digital nationalism takes root in everyday life, reshaping our fundamental understandings of nationhood, the public, and the other.